Who Can Afford ‘Affordable Housing’ in Santa Barbara?

As Rent Prices Increase, Low-Income Renters Compete for Dwindling Supply of Below-Market Rentals

Tue Sep 12, 2023 | 6:50pm

This week, Santa Barbara had its 15 minutes of shame when S Money, an Australian-based money exchange service, ranked the city as the “most expensive city to be happy in the U.S.,” claiming that — according to a “price of happiness” index based on a 2018 Purdue University study on the relationship between happiness and income — it costs about $162,000 a year to be happy in Santa Barbara.

The rankings, which placed Santa Barbara in the dubious top spot above Honolulu, New York City, and San Francisco, went viral and sparked a wave of online criticism, but the report also highlighted a larger problem underlying Santa Barbara’s extremely high cost of living: If it costs that much to be happy in Santa Barbara, how much does it cost just to exist?

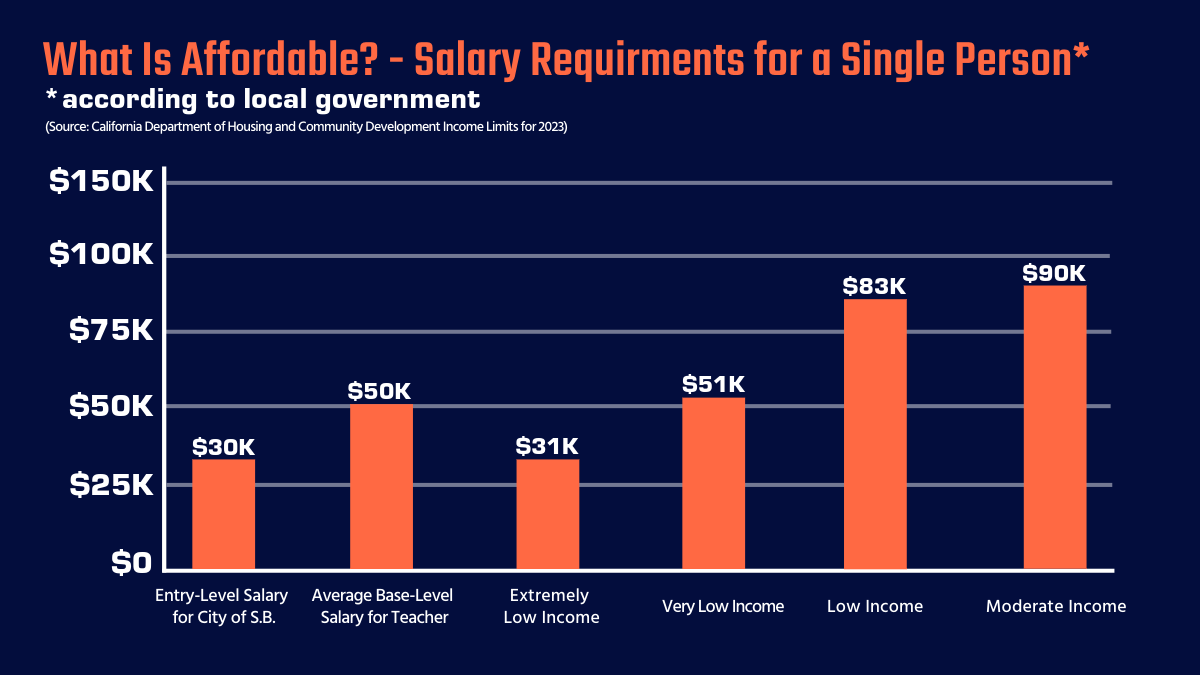

According to the recently updated income limits from the California Department of Housing and Community Development, the Area Median Income (AMI) for Santa Barbara County jumped up from $101,000 per year to $107,300 for a four-person household.

Under the new limits, any person earning under $31,050 a year (the average salary for an entry-level position in Santa Barbara is $25,000-$30,000) would be considered “extremely low income.” Those earning up to $51,800 a year, around the starting salary of a schoolteacher, would be “very low income,” and anybody making less than $82,650 a year could qualify as a low-income renter.

These changes have squeezed the already dwindling supply of affordable housing in Santa Barbara, forcing longtime low-income renters to compete against those who would be considered middle class in other areas. This is compounded by the fact that the city has had a problem getting private developers to build any more affordable housing than the 10 percent of units mandated for large residential projects.

Making things worse, the city is dragging far behind its previous goals for affordable housing. In the latest 2023 Housing Element — which outlines how the city will accommodate 8,001 more units of housing in the upcoming 2023-2031 cycle — statistics show that just 1,824 units of housing have been built during the previous cycle, or about 44 percent of the state’s allocation of 4,100 units.

But the statistics show a shocking discrepancy when separated into market-rate and lower-income housing. While 97.5 percent of the market-rate housing goals have been met, with nearly 1,600 units of above-moderate-income housing built from 2015 to 2022, there has been a severe lack of very-low-, low-, and moderate-income housing built over that same period. Altogether, only 247 units were built for all lower-income brackets combined, just more than 8 percent of the state’s allocation of 2,834 units.

The Housing Authority of the City of Santa Barbara is one local agency fighting for what’s known as “capital A” affordable housing — or residential projects created in partnership with state and regional governments to fill the need for all types of affordable housing.

When private developers submit applications with 40 units of housing boasting four “affordable units,” those units can refer to anything available to tenants with “moderate income” or below, including those making anywhere from 80 to 120 percent of the AMI (up to $128,60 per year). But projects done through the Housing Authority are able to leverage city and federal funding to build projects that can promise 100 percent of units to all lower-income brackets, with rents that are limited by state and regional guidelines.

In August, the Housing Authority had two affordable-housing projects approved by the city that will provide 111 units of below-market housing in the downtown area. The first is a 63-unit development at 400 West Carrillo Street, which will be 100 percent rent-restricted to low- and moderate-income renters and was unanimously approved by the city’s Planning Commission on August 10. The second, a 48-unit project at 220 North La Cumbre Road that will be available exclusively to very-low- and low-income families, received final approval from the city’s Architectural Board of Review on August 21.

Housing Authority Director Rob Fredericks said that the rents for all affordable housing projects are set by federal guidelines based on the income of the tenants. For renters, this means paying no more than 30 percent of your income on rent, factoring in the size of the household.

For a single person making $82,950 a year, the new income limit for low-income renters, this translates to $2,074 a month, or around $1,450 a month for a studio apartment. For a two-person household bringing in $94,800 a year, also considered low-income, the rent for a one-bedroom would be $1,896.

At the same time, the rate of renters paying more than a third of their income on rent is growing. According to the state’s latest figures, more than half of the city’s 20,000-plus renters are paying more than 30 percent of their income on rent, with a quarter of the city’s renters paying more than 50 percent of their money on rent alone.

For housing advocates in Santa Barbara, the need for affordable housing and drastic inflation of rent prices are at emergency levels, and some are urging city and county leaders to do more to tackle the problem, whether that be supporting agencies like the Housing Authority with more resources to continue building for low-income families or drafting rental protections in the meantime.

“Our skyrocketing rents and our dismal vacancy rate are pushing people out at an alarming rate — it’s unrelenting and unjust,” said Stanley Tzankov, cofounder of the Santa Barbara Tenants Union and housing advocate with the Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE). “It’s unraveling the social fabric that makes our city and region vibrant, diverse, healthy, and sustainable.”

“And yet there are totally things we can do at the local and regional level to meaningfully address it,” he continued. “The city can and absolutely should stop dragging its feet and finally pass long-overdue, bold, and broadly popular tenant protections like rent stabilization and a rental registry; they should stop approving expensive hotels and luxury second homes and instead zone, help finance, and fund housing that’s truly affordable, near jobs, and in transit corridors.”